Behind the scenes Ė Nordunís Way

The inspiration for the Nordun’s Way Series

Some days, I have to remind myself where it all began. It was in 2018, with this young lady called Nordun, my gorgeous and extremely naughty niece from Tibet. She is the one that inspired me to write the first book in the Nordun’s Way series, The Horsemaster’s Daughter, set in 13th C Tibet.

In 2018, my husband and I were fortunate to obtain a Visa to visit his family in Tibet. My husband had left his home in 2004 to study in India and hadn’t seen his family for all those years. We spent three months with the family in Kham, visiting all the relatives (and there are many!) and also some of the beautiful places around.

One day we were at the horse races, and I realized there were no women riding. My niece Nordun had told me before she’d wanted a horse forever, but her father wouldn’t let her have one.

One day we were at the horse races, and I realized there were no women riding. My niece Nordun had told me before she’d wanted a horse forever, but her father wouldn’t let her have one.

I told my brother-in-law I was surprised to hear that no women took part in the races. “Of course not,” he replied. “Horses and girls don't go together, never have, never will.” Yes, that’s what he said. Right there and then, the character of Nordun formed in my mind.

Coming home after three magical months, I put pen to paper, wanting to write a little story about a girl riding a horse, just for Nordun. But somehow the little tale turned into a full-fledged series about a young woman blazing her own trail through the turbulent times of thirteenth century Tibet.

By the time I finished The Horse Master’s Daughter (Book One), my brother-in-law had gotten himself a pregnant mare (a good deal for a trade he had made, he said). And when I finished Echoes of Home (Book Three), the mare had given birth to not one, but two beautiful little horses!

Coincidence? I don’t think so…

Oh, and the horses are here to stay, as my brother-in-law built a brand new stable next to his house—he's as smitten with them as Nordun is!

I’ve always had this thing for high mountains and remote places. And a passion for education—which I believe is the key to empowerment for both women and men.

I’ve always had this thing for high mountains and remote places. And a passion for education—which I believe is the key to empowerment for both women and men.

I’ve considered myself very lucky—being the first generation in my family to go to college – and in 2006 I decided to pass on my good fortune. I went to volunteer as a teacher at Jampa Choling, a tiny Tibetan Buddhist monastery for nuns in Himachal Pradesh, the Indian Himalayas.

I fell in love with the place and the people, and came back many times—as a teacher and a student—and spent long periods with these high-spirited women on their remote mountaintop, relishing the solitude and contemplative life.

I fell in love with the place and the people, and came back many times—as a teacher and a student—and spent long periods with these high-spirited women on their remote mountaintop, relishing the solitude and contemplative life.

I even did a PhD on the daily lives of these nuns and their sisters in the Himalayas, just to spend as much time with them as possible.

To this day their dedication to the Dharma, to live their life in service of all sentient beings, often against all odds, is an enormous inspiration for me, and many of the lessons Nordun learns on her way are those I’ve been taught by the nuns on their mountain.

Facts and Fiction in the Nordun’s Way Series

When I visited my Tibetan in-laws, my (now late) father-in-law told me many stories about the family history, but also about the history of their village and Kham. When he told me their village name derived from the Mongolian fort that once stood there in medieval  times, my mind jumped. Mongols. Middle Ages. I had always had a fascination for the Mongol Empire and its Qa’ans. Although the power-thirsty Mongol Qa’ans spread death and destruction in their tracks across Eurasia, they also facilitated an incredible exchange of people, goods and ideas, considerably expanding Old World horizons. So when it came to pick a time period for Nordun’s Way, I decided on the period when Tibet was part of the Mongolian empire under Qubilai Qa'an, but was safe enough to travel the routes I had in mind for Nordun and her companions.

times, my mind jumped. Mongols. Middle Ages. I had always had a fascination for the Mongol Empire and its Qa’ans. Although the power-thirsty Mongol Qa’ans spread death and destruction in their tracks across Eurasia, they also facilitated an incredible exchange of people, goods and ideas, considerably expanding Old World horizons. So when it came to pick a time period for Nordun’s Way, I decided on the period when Tibet was part of the Mongolian empire under Qubilai Qa'an, but was safe enough to travel the routes I had in mind for Nordun and her companions.

Since 1244, the Tibetan region was structurally, militarily and administratively under control of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, but kept a degree of religious political autonomy under a lama from the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. Although there were always wars and uprisings in the Mongolian empire, 1285-1290 was a time when the situation in Tibet and surroundings was settled enough to travel, so I decided on that period.

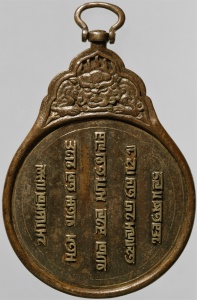

Moreover, during this period, travel and trade was very much encouraged and facilitated by the Mongol Qa’ans. The Mongolians valued luxury items so much, Mongolian laws prohibited under penalty of death for travelers being harmed during their journeys to trading posts in Mongol-ruled territories. In order to allow outside traders access to goods, one of the world’s first passports called the peisa (i.e., sign or card in Chinese) was developed and postal relay stations were extended in order to expedite the transmission of mail, officials, military, traders and foreign guests.

To stimulate trade even more, the Mongols elevated the class of a trader to that of an ortagh who acted as a business man or merchant to allied nations and represented a wealthy Mongol. They typically enjoyed greatly reduced tax rates and respect, which resulted in increased trade and collaboration between merchants. In Book Three, you’ll come across Xia and her Mongolian husband being a member of this class of traders.

To stimulate trade even more, the Mongols elevated the class of a trader to that of an ortagh who acted as a business man or merchant to allied nations and represented a wealthy Mongol. They typically enjoyed greatly reduced tax rates and respect, which resulted in increased trade and collaboration between merchants. In Book Three, you’ll come across Xia and her Mongolian husband being a member of this class of traders.

The Mongolians highly valued silk for their clothing, wall hangings, and furnishings, and coveted artistic motifs from Japan and Tibet, and tea nearly outstripped the silk trade. Next to luxury items, the Mongols desired to advance their knowledge in the areas of medicine, agriculture, religion, astronomy, craftsmanship, and technology. As such, scrolls and books on these subjects were transported to and from the Middle East and China—scrolls like the spell book the ngakpa holds in Book One, and the phrase book and the Book of Buddha’s Names are Karma gifts to Nordun in Book Two and Book Three.

The Mongol Qa’ans favored Buddhism, but were also very tolerant towards other religions. Curiosities involving different religions allowed the transposition of Buddhism, Islam and even Christianity in the Middle East and China. You’ll read about this diversity of religions from book three onwards where Nordun has her first encounter with Islam, visiting a Muslim temple in Chang’an. Besides the freedom of religion, this was also a time where women from wealthy families were known to hold prominent positions in the family trade. You’ll find some fine examples of this meeting Lanying in Book Two, and Xia in Book Three.

As a historian, I wanted to get the “historical background and details” right. I should have known better. I did extensive desk research and consulted experts in the field and was reminded—as my professors already did thirty years ago—that my noble pursuit of “historical accuracy” was nearly impossible. There’s no consensus about the historical accuracy of this period in time, for history is obscured by the ones who wrote it down. At present, the Secret History of the Mongols (the only major narrative in Mongolian from the period of the Mongol Empire), is by many regarded essentially propaganda, not history, and there is a great deal of debate on the generally accepted account of the “history” of the Mongol Empire. It would take too much academic analysis to explain exactly why this is, but, briefly, the issue is that a lot of reliance has been placed on Persian accounts of Mongol history while there is a huge amount of source material in Chinese which has scarcely been touched. There’s still so much to be discovered about this fascinating time in history, and I’m following the academic debate with great interest.

Not much is known about the exact villages/settlements and their names in Tibet at that time. Therefore, I have taken the liberty to incorporate some of the villages/cities that exist in Tibet at present time.

This brings me to a last note on facts and fiction—transliteration. For readability purposes, I’ve used the (phonetic) Romanized transcription whenever Tibetan terms, personal names or place names are mentioned, and I’ve transcribed the Chinese terms, personal names and place names in pinyin.

Placing the facts into the fiction

I always come across amazing things doing research. Here are some of the artifacts, places, and people that I’ve given a place in the Nordun’s Way Series.

Divination—Tibetans have been relying on divination for centuries to give insight into the future turns of events, undertakings, and relationships and is still used on a daily base. Divination can be done with various objects like dice, bootstraps, prayer beads and animal bones.

Divination—Tibetans have been relying on divination for centuries to give insight into the future turns of events, undertakings, and relationships and is still used on a daily base. Divination can be done with various objects like dice, bootstraps, prayer beads and animal bones.

In The Horse Master’s Daughter, Dechen uses her prayer beads (Book One), and the ngakpa uses a simple method involving two rolls of dice to reveal one of the thirty-six possible outcomes described in an ancient text. Here you see a modern Palden Lhamo Mo set up of this method. On the left hand side are the bell and dorje, used in preliminary prayer. The three dice on the left are inscribed on the six sides with OM AH RA PA TSA NA DHI. The Lapis Lazuli dice on the right are regular 1-6 dice.

Pic by @buddhaweekly

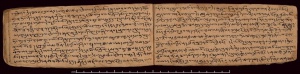

Spell book (Book One) I already knew I wanted to incorporate a spell in The Horse Master’s Daughter. Looking for spells, I came across the academic blog from Sam van Schaik, Head of the Endangered Archives Programme at The British Library. [link - https://earlytibet.com/2009/02/19/a-tibetan-book-of-spells/

Spell book (Book One) I already knew I wanted to incorporate a spell in The Horse Master’s Daughter. Looking for spells, I came across the academic blog from Sam van Schaik, Head of the Endangered Archives Programme at The British Library. [link - https://earlytibet.com/2009/02/19/a-tibetan-book-of-spells/

] where he mentions this manuscript from the Tibetan Book of Spells, Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, China, ca. 9th to 10th century, at the British Library. Needless to say, I found it a perfect match for the ngakpa. (Pic by @britishlibrary)

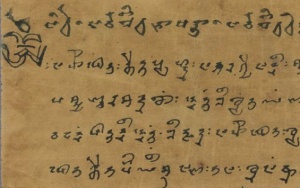

Phrase Book (Book Two)—As I read Van Schaik’s blog, I was intrigued by the Silk Road Phrase books. [Link https://earlytibet.com/2014/05/12/silk-road-phrasebooks/] He mentions one Tibetan-Chinese phrase book (found in Or.8210/S.1000 and S.2736) compiled for merchants, giving the Tibetan word, followed by the Chinese equivalent, all in the Tibetan script. This phrase book I wrote into A Pilgrim's Heart, as a gift from Karma to Nordun. To “spice things up” a bit, I combined this with the Khotanese scroll he mentions in the same article, which tells about the gossip on the Silk Road.

Phrase Book (Book Two)—As I read Van Schaik’s blog, I was intrigued by the Silk Road Phrase books. [Link https://earlytibet.com/2014/05/12/silk-road-phrasebooks/] He mentions one Tibetan-Chinese phrase book (found in Or.8210/S.1000 and S.2736) compiled for merchants, giving the Tibetan word, followed by the Chinese equivalent, all in the Tibetan script. This phrase book I wrote into A Pilgrim's Heart, as a gift from Karma to Nordun. To “spice things up” a bit, I combined this with the Khotanese scroll he mentions in the same article, which tells about the gossip on the Silk Road.

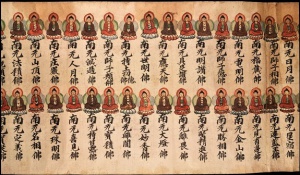

Book of Buddha’s (Book Three) – Diving the rabbit hole of historical book research, I came across this beautiful 9th/10th century scroll "Book of Buddha's Names" with a small painted Buddha at the start of each line. This scroll was discovered in one of the Dunhuang Caves, China. I was sure Nordun would have loved it—so I gave it to her in Book Three. (Pic by @britishlibrary)

Book of Buddha’s (Book Three) – Diving the rabbit hole of historical book research, I came across this beautiful 9th/10th century scroll "Book of Buddha's Names" with a small painted Buddha at the start of each line. This scroll was discovered in one of the Dunhuang Caves, China. I was sure Nordun would have loved it—so I gave it to her in Book Three. (Pic by @britishlibrary)

Karma’s tattoo (Book One) Checking out Mongolian culture I came across this intricate tattoo of a deer with a griffons beak and Capricorn antlers found on the body of an ancient Siberian princess. This tattoo was the inspiration for Karma’s tattoo.

Karma’s tattoo (Book One) Checking out Mongolian culture I came across this intricate tattoo of a deer with a griffons beak and Capricorn antlers found on the body of an ancient Siberian princess. This tattoo was the inspiration for Karma’s tattoo.

Nordun’s Blue Poppy coat (Book Two) - Researching the Himalayan flora, the blue poppy appeared on my screen.

Nordun’s Blue Poppy coat (Book Two) - Researching the Himalayan flora, the blue poppy appeared on my screen.

It’s a small but powerful flower with great healing properties—it’s slightly poisonous when used too much, but it promotes blood circulation to remove blood stasis and eases pain at the same time.

A great color and great cure, so when it came to decide on Nordun’s coat, poppy-blue it was.

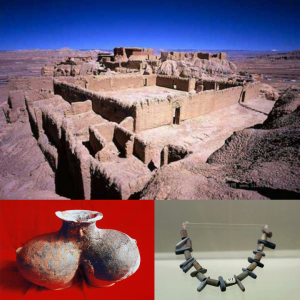

Nordun’s beads for Karma from the Karub or Kanuo ruins (Book Two)– Nordun and Karma visit the Karub ruins, one of the three major Tibetan primitive cultures ruins. They are located in the town of Karub, Chamdo County and belong to the Neolithic era settlement ruins, dating back between four and five thousand years ago.

Nordun’s beads for Karma from the Karub or Kanuo ruins (Book Two)– Nordun and Karma visit the Karub ruins, one of the three major Tibetan primitive cultures ruins. They are located in the town of Karub, Chamdo County and belong to the Neolithic era settlement ruins, dating back between four and five thousand years ago.

Looking at pictures of the paired pottery jars and other items excavated, the idea for Nordun’s gift to Karma came to me. The finds are 4200 to 5300 years old and are exhibited within the Museum of Tibet. (Photo m.tibet.cn)

Dugmo, King Gesar's scorned wife (Book Two) Hell has no fury like a woman scorned, they say. Well, history has a lot of woman scorned like the immortal Dugmo, King Gesar's wife who is said to have taken up eternal residence at the bottom of the holy lake of Yilhun Lha Tsoa which Nordun visits in A Pilgrim's Heart.

Dugmo, King Gesar's scorned wife (Book Two) Hell has no fury like a woman scorned, they say. Well, history has a lot of woman scorned like the immortal Dugmo, King Gesar's wife who is said to have taken up eternal residence at the bottom of the holy lake of Yilhun Lha Tsoa which Nordun visits in A Pilgrim's Heart.

After Dugmo was rejected by King Gesar for a minor infidelity she committed, she left and travelled all alone through Tibet. Then she fell in love with the beautiful landscape of the lake and its surroundings. She could not turn back on this beautiful landscape and decided to stay there forever. As usual, there are not many illustrations or statues of scorned women. This one is taken in Sengdruk Takse palace, rebuild in Golok at the place designed by Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok as the place of the ancient palace of King Gesar by @tibet.justice.paris

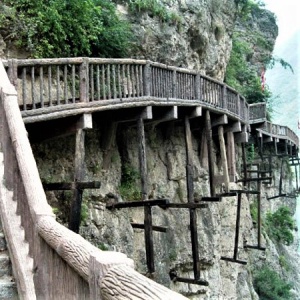

The Shu roads (Book Three) - I roamed many remote roads in the high Himalayas, but never the Shu roads in China that Nordun takes from Tibet to Chang'an (Xia'an). The Shu Roads were a system of mountain roads, consisting of wooden planks erected on wooden or stone beams along the steep cliffs and mountain sides. Built in the 4th century BC to join Shaanxi and Sichuan provinces, they got their name from the State of Shu (c. 1045-316 BC), which was in modern-day Sichuan Province.

The Shu roads (Book Three) - I roamed many remote roads in the high Himalayas, but never the Shu roads in China that Nordun takes from Tibet to Chang'an (Xia'an). The Shu Roads were a system of mountain roads, consisting of wooden planks erected on wooden or stone beams along the steep cliffs and mountain sides. Built in the 4th century BC to join Shaanxi and Sichuan provinces, they got their name from the State of Shu (c. 1045-316 BC), which was in modern-day Sichuan Province.

Li Bai (701-762), a famous poet in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), once said: “Walking on the narrow Shu Roads is more difficult than climbing up to Heaven.”

Here's a pic of the famous Mingyue Gorge Gallery Road—can't wait to visit myself! (Picture accesschinatravel.com)

Chinese peonies (Book Three) - Getting the details for Book Three right, I had to look up some Chinese peonies which you will find in and around the houses mentioned in Echoes of Home. Long before the tulip mania of 17th century Holland, there was peony mania in China where tree peonies were well established in the Chinese cultural esthetic as symbols of female beauty, and love and well as wealth and status.

Chinese peonies (Book Three) - Getting the details for Book Three right, I had to look up some Chinese peonies which you will find in and around the houses mentioned in Echoes of Home. Long before the tulip mania of 17th century Holland, there was peony mania in China where tree peonies were well established in the Chinese cultural esthetic as symbols of female beauty, and love and well as wealth and status.

Why did peonies become so popular? Well, legend has it that one chilly winter morning an empress who was as beautiful as she was capricious used her magical powers to order all the flowers in the imperial garden to blossom.

Each of the flowers, fearing the wrath of the Empress, obeyed her whim, except one, the peony!

Shaken by the flower’s impudence, the Empress ordered her servants to move all the peonies of the realm to the coldest, most distant reaches of the Empire.

But the peony withstood the cold, inhospitable climate, bringing forth its gloriously colored blossoms for all the world to see. Realizing that she had been defeated by the strength and determination of the peony, the Empress allowed it to return from exile, crowning the plant the “Queen of All Flowers”.

Personally peonies are my favorite flowers—even though I'm from Holland and surrounded by the most gorgeous tulips. I can't wait till its peony season here again! This beautiful painting is by the female painter Gu Shao from the Qing Dynasty. (Photo zhejiangmuseum.com)

The story of Zhuo Wenjun and Sima Xiangru (Book Three) - I’m always looking for classic tales of love with a clever, kick-ass women and the story of Zhuo and Sima is certainly one of these.

The story of Zhuo Wenjun and Sima Xiangru (Book Three) - I’m always looking for classic tales of love with a clever, kick-ass women and the story of Zhuo and Sima is certainly one of these.

Zhuo, a clever young widow made the firm decision about chasing her love regardless of her parents’ disapproval. When they fell into hardship, she cleverly started a wine shop to alter their difficult financial condition. Eventually, Sima came into money and turned his back on Zhuo, but instead of simply tolerating his behavior, she won her husband’s love back with her sincere poetry. Now if that isn't love...

Even though the story is at least 2200 years old, Zhuo is still widely quoted in China today as an example of a brave and clever woman chasing love and protecting her marriage, and how lucky was I to find Zhuo lived on the route Nordun takes to Chengdu.

This picture is of the statue featuring Zhuo Wenjun and Sima Xiangru in the culture park of Taihu County, Anhui Province. (Photo shine.cn)

A fierce Chinese guardian lion (Book Three) - Chinese or Imperial guardian lions are a traditional Chinese architectural ornament and you will read about them in Echoes of Home as protectors of the houses. Typically made of stone, these are also known as stone lions or shishi (石獅、shíshī), or in colloquial English as lion dogs or foo dogs/fu dogs.

A fierce Chinese guardian lion (Book Three) - Chinese or Imperial guardian lions are a traditional Chinese architectural ornament and you will read about them in Echoes of Home as protectors of the houses. Typically made of stone, these are also known as stone lions or shishi (石獅、shíshī), or in colloquial English as lion dogs or foo dogs/fu dogs.

The lions are usually teamed up in a pair in front of the doorway—often one male with a ball and one female with a cub—and were thought to protect the building from harmful spiritual influences and harmful people that might be a threat. This gorgeous one is dated back to the Yuan Dynasty. (Photo @barakatgallery)

Xia’s dress (Book Three)—I’m always looking for fashion inspiration and here’s a woman's jacket with Manchijiao pattern of lotus pond and other vignettes, dated 1312, Yuan dynasty, China. It’s silk embroidery on silk gauze and the inspiration to Xia’s dress in Echoes of Home.

Xia’s dress (Book Three)—I’m always looking for fashion inspiration and here’s a woman's jacket with Manchijiao pattern of lotus pond and other vignettes, dated 1312, Yuan dynasty, China. It’s silk embroidery on silk gauze and the inspiration to Xia’s dress in Echoes of Home.

(Photo @metmuseum)

Mosque in Chang’an (Book Three) I was delighted to discover there's been a mosque in Xian since the 7th C, with a vibrant Islamic community—and yes, I just had to include this in the storyline of Echoes of Home.

Mosque in Chang’an (Book Three) I was delighted to discover there's been a mosque in Xian since the 7th C, with a vibrant Islamic community—and yes, I just had to include this in the storyline of Echoes of Home.

The Great Mosque as it stands today in Xian (pic here) is not the one from the 7th C, but was begun in 1392. Unlike the mosques common to Arab countries, this mosque has neither domes nor minarets. The style is almost wholly Chinese, except for the Arabic lettering and decorations that list the 99 names of God and verses from the Koran. (Photo: LMSpencer/Shutterstock).

Elles Lohuis

Elles Lohuis